New Essay: Critique of the Week: David Brooks

In this column I offer constructive critiques of public figures I admire by pointing out how they could benefit from a developmental perspective.

For the past twenty years, political and social commentator David Brooks has been an influential voice in American culture. At times, I’ve found his opinions to be timely and even inspirational. But I also often find myself balking or groaning at his views. The middle-brow accessibility of his writing helps him speak to a wide audience. Yet it’s this same accessibility that prevents him from being taken seriously in many intellectual circles. I do, however, take Brooks seriously and thus offer the following constructive critique.

Brooks occupies a rather unique niche in America’s cultural landscape. He rose to the top of the media’s commentariat in the early 2000s—gaining a high perch at both The New York Times and the PBS Newshour—by articulating a genteel form of moderate conservativism that the liberal clerisy found acceptable. And until 2016, Brooks’ espoused political positions could mostly be classified as “center right.” But since the election of Donald Trump, his views have changed considerably. While he continues to be despised by many on both the left and the right (which is perhaps good sign), I would not label him a centrist by default. This is partially because “centrism” is no longer a coherent position in our contemporary political environment. As the growing power of progressivism has eroded the legitimacy of “viewpoint diversity” at both The Times and the PBS Newshour, Brooks has tried to stakeout a position on what might perhaps be identified as the “right edge of the left.” Yet because this rather tenuous position on liberalism’s right margin continues to move left, Brooks finds himself increasingly constrained in what he is able to say without risking the loss of his lofty position in the prestige economy.

A recent example of how Brooks’ must now walk on eggshells when talking about the culture war was seen in his remarks on the April 22nd edition of the Newshour. When asked to comment on the state of America’s culture war, Brooks said:

If you look at the World Values Survey, which surveys values all around the world, what you find is that people in the English-speaking world and in Protestant Europe, our values are shifting. … values where people like I live, urban, educated, shifting. A lot of the rest of the country, not shifting. And so we’re just seeing widening chasms on values on a whole range of issues, when to teach sexuality to schoolkids. And, somehow, we have to have that fight without it being dominated by the crazies. … We need to have a discussion about this stuff. And, right now, it’s being submerged, because it’s been hyper-politicized. And when you turn a discussion about difficult issues into partisan politics, you have destroyed it.

Watching the discussion, I was initially excited to hear Brooks cite the World Values Survey and identify shifting values as the underlying cause of the culture war. But while Brooks came tantalizingly close to articulating the heart of the problem—and thus the key to its solution—his analysis stopped short of addressing the larger implications of America’s evolving values. In fact, Brooks’ use of a noncommittal word like “shifting” to describe the cultural transformation of a major portion of American society over the last few years seems to be a dodge.

As the World Values Survey makes clear, the values held by America’s elites are not merely shifting, they are developing. Over the last fifty-years, a new form of culture—“the progressive postmodern worldview”—has gradually emerged in American society. This progressive worldview has continued to gain ground in elite circles to the point where it now supplies the accepted moral norms for most of America’s new “establishment.” Progressivism has effectively won the culture war by championing greater inclusivity, sensitivity, and deep concern for those who have been victimized or marginalized. In the minds of many of our best and brightest citizens, these caring values seem to offer a way to create “the more beautiful world our hearts know is possible.” And even those who can see the abiding threats and downsides of progressivism’s growing power do well to appreciate why this worldview has attracted so many good people, especially the young, into its ranks.

Brooks admits that, along with most of his peers in the mainstream media, his values have shifted in a progressive direction. Yet by characterizing his change of mind, not as form of growth or maturation into something higher, but as merely an adjustment along an implied horizonal continuum, he reveals how he remains conflicted about falling into step with America’s “progressive turn.”

In 2015, prior to his personal progressive turn, Brooks was more comfortable with the idea of a developmental hierarchy of values. Calling for a moral revival, and lamenting relativism and the erosion of social norms, he wrote: “[Our] norms weren’t destroyed because of people with bad values. They were destroyed by a plague of nonjudgmentalism, which refused to assert that one way of behaving was better than another. People got out of the habit of setting standards or understanding how they were set.”

Now, however, he has come to frame the worldview of liberal modernity as a curious global outlier:

We in the West subscribe to a series of universal values about freedom, democracy and personal dignity. The problem is that these universal values are not universally accepted and seem to be getting less so. … The critiques that so many people are making about the West, and about American culture — for being too individualistic, too materialistic, too condescending — these critiques are not wrong.

I do agree that “these critiques are not wrong,” but I firmly believe that liberal values will eventually become “universal” over the course of cultural evolution. Brooks, however, now seems less sure about both the superiority and inevitability of liberal modernity. While he continues to champion Western values, he seems increasingly unwilling to characterize these values as “more developed” than the premodern world’s “emphasis on communal cohesion.”

I sympathize with Brooks’ dilemma, but I think he deserves to be criticized for his failure to provide better thought leadership in this turbulent time of hyperpolarization. Brooks’ visibility and influence make him ideally placed to bring greater clarity to both the causes of the culture war, and its potential solutions. And Brooks’ muddled view of our national schism would indeed be clarified were he willing to recognize and affirm a vertical dimension of moral development in which the evolution of values moves in the direction of greater inclusivity.

Adopting such a developmental perspective provides both a validation and critique of progressive values. Progressives have done well to help widen our society’s “circle of care” to better include those who have been left behind. Yet at the same time, by rejecting viewpoint diversity and showing contempt for those who disagree with them, progressives reveal how their own worldview is not inclusive enough to serve as the enlarged cultural container we need to overcome America’s debilitating hyperpolarization. If Brooks were to adopt such a developmental perspective, his commentary could provide the clarity we need by explaining how the “widening chasm on values” he describes is resulting from America’s cultural growth—and thus how our further growth can provide a remedy.

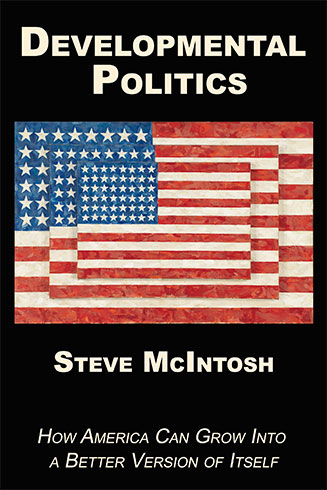

This developmental perspective, which is championed by the think tank I lead, helps explain how progressivism has gained traction by pushing off against the negative externalities of liberal modernity. The emergence of the progressive worldview is thus following a well-established evolutionary process wherein development unfolds through the appearance of internal contradictions within established structures. These internal contradictions can be destabilizing, but they can also stimulate authentic growth—the emergence of a larger, richer whole brought about by the resolution of these oppositions at a higher level. This dialectical process of development is sometimes simplified as thesis-antithesis-synthesis.

Viewing America’s culture war through this kind of developmental lens reveals how progressive postmodernism has gained power by staking out a position of antithesis to America’s previously established culture. And this same developmental perspective also reveals the potential for the next step—a synthesis—which is now appearing on the horizon of history. The logic is simple: progressive postmodernism is not the end of history. In the same way that progressivism comes after modernity, something else in turn will come after progressivism.

This next step in America’s cultural evolution can deliver the synthesis we need by doing what progressivism cannot—by including all Americans of good sense and good faith within a larger “we.” Americans can accordingly begin to create such an expanded cultural container by coming to appreciate how the best aspects of both the left and the right are ultimately interdependent.

In his Newshour comments quoted at the beginning of this column, Brooks urges Americans to meet in the middle and “have a discussion” without the “crazies.” But this seemingly sensible recommendation is ultimately unworkable because it assumes that we can simply glue the thesis and antithesis back together like humpty dumpty. It is, however, too late for that. Instead of seeking increasingly scarce common ground, in order to grow out of the culture war and heal our broken politics, we need to find a new kind of higher ground—a synthetic next step through which the values of America’s competing worldviews can be integrated and harmonized.

So rather than calling for a cultural retreat to a mostly nonexistent common ground, if David Brooks were to begin using a developmental perspective to advocate growth toward the synthetic higher ground we need, he could provide the courageous thought leadership called for by our perilous moment in history.